Apartment hunting in Brooklyn earlier this year was the predictable nightmare.

I saw a place on Fifth Street that looked perfectly acceptable except that it had no closets. Not one.

by Paula Span

Apartment hunting in Brooklyn earlier this year was the predictable nightmare.

I saw a place on Fifth Street that looked perfectly acceptable except that it had no closets. Not one.

by Paula Span

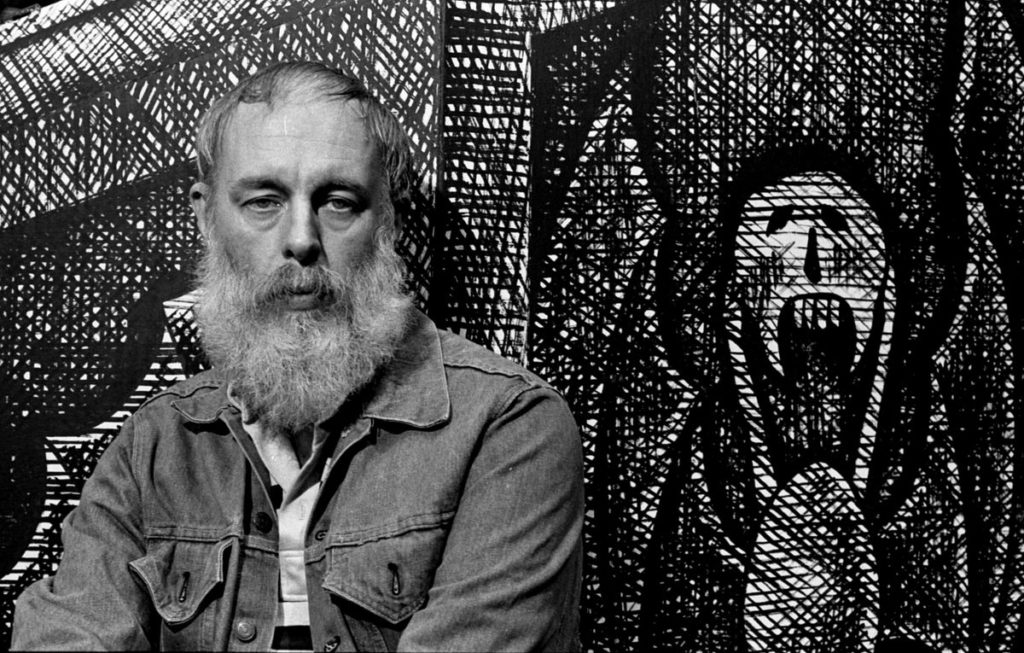

On a June day too dank for the beach, a three-generation carload of Goreyphiles—fans of the American author, illustrator, and oddball genius Edward Gorey—pulled into a small parking lot in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts.

The Edward Gorey House, a sea captain’s home the artist bought in 1979, is now a museum that welcomes visitors from April to December each year. Gorey slowly reclaimed it from rot and ancient plumbing, and lived and worked here until his death in 2000. I was the senior member of the group, and one with a history here, a history that involved Gorey himself.

by Paula Span

3:45 AM: Amal “Molly” Kaydouh gets up in the dark. Padding around her North Arlington apartment on this Tuesday morning, she reaches for one of her five identical red shirts appliqued with the Nevada Diner’s logo, along with a black apron, leggings and, crucially, non-skid shoes. She brightens the ensemble with sparkly earrings and painstakingly applies makeup, because appearance counts.

Driving to the diner in Bloomfield, she stops at a Dunkin’ Donuts for an espresso and smokes a single Salem menthol in her car. By 6 am she’s on the job, cleaning every surface in the back room—tables, booths, saltshakers. She makes pots of coffee and restocks bins of ketchup packets and plastic Cream-O-Land containers.

And then she waits.

by Paula Span

The exercise studio I’ve patronized for 30 years had to shut down, of course. So I switched to 40-minute walks through my suburban neighborhood and around the perimeter of the nearby park, since the park itself was also now off-limits.

That would provide the necessary cardiovascular workout, but what about keeping my core firm, my finicky back unclenched, my flexibility intact? I unrolled a yoga mat on the bedroom floor and added a daily 20-minute hodgepodge of crunches, knee bends, asanas, balance poses and, um, improvisations.

by Paula Span

On my first British morning, a dank one like all that followed, I took the tube to Leicester Square and walked up Charing Cross Road. It was surprisingly quiet, the rush hour over and the musty bookstores along Charing Cross not yet open for business.

In five minutes, less, I reached Cambridge Circus, one of those disorienting agglomerations where several London thoroughfares converge and then meander off again. And there it was on the right between Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue, a sturdy-looking Edwardian edifice, red brick garnished with beaded stonework.

Naturally, no sign or nameplate identified the place. The Circus is so sensitive a location, its creator has written, that its occupants never allow their taxis to pull up at the entrance. They disembark in front of the ornate theater across the street instead, or at Foyle’s bookstore a block north. But I had spent weeks reading and taking notes and poring over detailed street maps. I had also, after a series of transatlantic and domestic faxes resulting in a phone call at a certain time on a certain day, consulted with John le Carre.

by Paula Span

The memorial service proved a study in numbed, dignified restraint.

Reetika Vazirani was so warm and open, so brilliant, so beautiful, a procession of mourners said, taking the lectern to share their recollections. Reetika, the gifted, painstaking poet; the encouraging but rigorous teacher; the magnanimous friend. And her son, Jehan, such a captivating 2-year-old. A sprite attending a grown-up friend’s party in a wizard’s cape. A wonder, learning his colors in Spanish — azul, amarillo, verde. In the photos displayed at the entrance to the room — in which he rode a carousel, perched atop a slide, or nestled on Reetika’s lap — he was always beaming.

Before long, the service last July at the National Press Club took on the feeling and cadences of a poetry reading. That was fitting: The room was full of poets, and poetry had given Reetika her place in the world. One friend chose Edna St. Vincent Millay. A colleague from William & Mary offered a few lines of Langston Hughes. A poem by Yusef Komunyakaa, Jehan’s father, began “I am five”; the friend who read it wanted to evoke an age Jehan would never reach.